Reflections on life as a children's author and illustrator in rural New York State.

Monday, December 13, 2010

Friday, December 10, 2010

The Children's Pony

The Children’s Pony

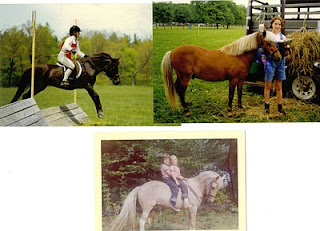

When I was three, and we were living in Loudonville, New York, our parents bought us a pony. She was a palomino Welsh pony, with a luxurious silver mane and tail. She had a triangular white patch on her near hindquarter. That marking made its way onto Thunder, the primitive horse in my novel, Wind Rider, as a sign that she was somehow genetically different, with a kind streak which allowed her to be tamed. To this day, Przewalsky horses are nearly impossible to train.

Our pony’s name was Primrose when she came to us, and she was quite naughty at first. I remember that my brother David thought up the name Maple Sugar and gradually she came to trust us and grow into her new name. She settled down to following my mother around like a big golden puppy and allowing all sorts of shenanigans like London Bridge under her belly and multiple children on her back. I truly thought I could ride her and embarrassed myself horribly when I told my teacher at Farm School (a magical nursery school) that I didn’t need to be led. You guessed it! The venerable old pony, Mickey Mouse, ran back to the barn with me at a trot! We did have one scare with Maple Sugar when she ran away down Border Road with my sister, Cathy, on her back. Like Mickey Mouse, she was probably thinking about her hay. Daddy was able to flag down a passing car, head her off, and catch her, and Cathy stayed in the saddle.

That summer, and for the next few years that we had her, we brought Maple to our camp on an island in New Hampshire, where my older brother, Ted, then ten or twelve, rode her on the old logging trails. When I later discovered the Billy and Blaze books by C.W. Anderson, I thought of Ted’s adventures riding his pony alone on the island. She learned to roll under the single strand of electric fence wire and visit Mrs. Fenn next door, who would open the kitchen window and hand her a few chocolate Hydrox cookies.

When we moved to Winchester, MA, in 1957, the fall of my fourth birthday, Daddy built a tiny stable for Maple in the back yard under the oak trees. Our grandparents came over to help and it was a big family project. Maple’s stable was a beautiful little building that stood until my parents passed away and the house was sold fifty years later. It had plank siding, a shingled roof, two windows, an overhang which allowed storage of a few bales of hay, and an electric light which worked from a big round, red battery on a little shelf by the door. I recall sitting in her manger on a winter’s day, methodically setting off a roll of caps from my brothers’ cap guns, one by one, by scratching each with a nail. Maple never minded. She just kept on placidly munching her hay and blowing steamy breaths into the cold air. We have a lovely home movie clip of Maple frisking in new snow on Christmas morning in the back yard.

I don’t really know what happened, but as many ponies do, Maple foundered. I remember the vet coming and big white horse pills which were probably the horseman’s common anti-inflammatory known as “bute.” (Butezaldone—hope my spelling is close I can’t seem to find it in Google.) Founder is a painful condition of the laminae of the hooves which causes lameness. Ponies can recover and be ridden again, but I think my mother was frazzled from raising four kids and felt she just couldn’t cope with a pony any more. In any case, Maple was given to Doris Spollett in Hampstead, NH. Doris was a NH representative in the days when few women were in politics. She loved horse and actually had her childhood pony and family carriage horse stuffed in the barn. She was going to breed Maple. We went to visit our pony once, and when all four children cried, Mummy said, never again. I was six.

Every Christmas after that, I asked for a pony. When my own children began begging for one, a fuzzy, round Shetland pony appeared in the goat pen one Christmas morning. His original name was Peanut. It was magical when the girls, then four and seven, chose Chestnut as his new name. Chestnut lived with us for about fifteen years before going to pony heaven. I am still working on a middle grade novel about him. He was always naughty, but we all loved him dearly. Sometimes he would rest his chin on my shoulder. He went to Pony Club Nationals for games twice and when Fern wanted to “be a cave girl for the summer,” was the inspiration behind Wind Rider. Like my golden childhood pony, Maple Sugar, he too was a Children’s Pony.

The Children’s Pony

We have a golden pony

With silver mane and tail

And Daddy built a house for her

With hammer saw and nail

Davy named her Maple Sugar

Teddy fed her hay

He’s big enough to ride alone

They saw a deer one day

Cathy’s toe got stepped on

It bled and made her cry

And Maple nudged her with her nose

As if to ask her why

I like to go and visit

In my snowsuit, boots, and hat

And sit up in her manger

For a cozy winter chat

We play London Bridges

Underneath her tummy

And she thinks chocolate cookies

At the house next door are yummy

We dressed her up as Pegasus

With cardboard wings and ties

And we were mad that day

Because she didn’t win first prize

She follows Mummy like a dog

And I’m not scared at all

With both fists buried in her mane

I know I couldn’t fall

Our cousins and the neighbors

And the dogs all run beside

And each child gets a turn

When we take Maple for a ride

Friday, December 3, 2010

An Ordinary Childhood

I'm still working on that title, but am simmering up a collection of rhymes about my childhood, 1953 through about 1965. We spent summers on a lake in southern New Hampshire. Maybe that's not so ordinary. We were damned lucky. We still are. My kids only had two weeks there each summer, but they are lake kids in their hearts. Our camp had well water piped to the kitchen sink, but my grandparents' camp had only lake water. My two brothers, Dave and Ted, my sister Cathy, and I were expected to fetch well water every few days for Grammy and Baba in gallon glass jugs.

The easiest way to fill them was from the faucet on the side of the pumphouse behind our camp. This was a little squat building of weathered boards nestled among ancient pines and hemlocks, on a path beside a Colonial-era stone wall. In May, pink ladyslippers sprang out of the pine needles like earthbound fairies. Until August, we battled swarms of mosquitos which thrived in the cool, moist air around the pumphouse.

The jugs were heavy. The good ones had a sort of glass tab which allowed one to use several fingers to carry them. The hard ones had only a ring for the index finger. As the littlest child, I was assigned a half-gallon jug with a tab. I remember being quite fond of my jug. As I grew, I could handle a full gallon like my big sister and finally a gallon in each hand like our bigger brothers. Our grandfather wanted us to develop a little muscle, I think, and didn't like to put the jugs in the cupboard or fridge with pine needls or sand on the bottom, so the challenge was not to set a jug down to rest on the five minute walk.

There was a greater challenge though. When a few gallons had been drawn from the tap, the pump would start up with a loud banging which sounded like: a-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel! My brothers were masters of terror and invented a little old man who lived in the pumphouse. They told Cathy and me that he resented us taking his water and hammered with his hammer to warn us away. If we took too much, he would burst out the door and come after us. I have a pretty clear image in my mind to this day of a wizened little man running after me with a hammer in his upraised had!

The twist to this horrible possibilty was that the boys were bigger and filled their jugs first. Just about the time their jugs were full, the pump would start up. they would run down the path, laughing, chanting: a-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel! along with the banging pump. Cathy and I were left quaking, sometimes even crying, yet more fearful of our our grandfather's rath if we didn't fetch our share of water. Even seeing our father go into the pumphouse to work on the pump, peering into that damp, cobwebby, half-underground, concrete chamber and seeing for ourselves that there was nobody at home, didn't entirely erase our fear. Until my grandparents finally had a well drilled at their own camp, my heart always thudded harder when the pump started up and The Little old Man in the Pumphouse started banging away with his hammer.

The Little Old Man in the Pumphouse

There’s a little old man in the pumphouse

My brothers both say that it’s true

But sometimes it’s fun to pretend to be scared

That he’ll jump out and run after you

The little old man in the pumphouse

Has skin that’s all mossy and green

And snaggley teeth and little mad eyes

He’s horrid and hairy and mean

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

He hammers with might and with main

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

Again and again and again

Who would be stealing my water—my icy-cold bubbling brew?

Children who dare

You’d better beware

Or I’ll hunt with my hammer for you!

There’s a little old man in the pumphouse

He pounds and he pounds with his hammer

We have to fetch water for Grammy and Baba

In spite of the clash and the clamor

Teddy and David are bigger

They make us girls fill our jugs last

And the hammer is pounding as loud as our hearts

As laughing they run away fast

Cathy can carry a big gallon jug

Switching hands without stopping to rest

Our brothers are strong, they can each carry two

But I like my half-gallon best

I can’t set it down because Baba will know

If there’s pine needles stuck to the wet

That drips down the glass on the side of my jug

Like icy-cold hot summer sweat

There’s a damp little room in the pumphouse

One time Daddy opened the door

And pulled on the string that turned on the light

I saw steps and the pump—nothing more

But the little old man in the pumphouse

Still hammers with all of his might

And tho’ I’m quite sure that he’s only pretend

He still makes me shiver with fright

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

He hammers with might and with main

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

Again and again and again

Who would be stealing my water—my icy-cold bubbling brew?

Children who dare

You’d better beware

Or I’ll hunt with my hammer for you!

The easiest way to fill them was from the faucet on the side of the pumphouse behind our camp. This was a little squat building of weathered boards nestled among ancient pines and hemlocks, on a path beside a Colonial-era stone wall. In May, pink ladyslippers sprang out of the pine needles like earthbound fairies. Until August, we battled swarms of mosquitos which thrived in the cool, moist air around the pumphouse.

The jugs were heavy. The good ones had a sort of glass tab which allowed one to use several fingers to carry them. The hard ones had only a ring for the index finger. As the littlest child, I was assigned a half-gallon jug with a tab. I remember being quite fond of my jug. As I grew, I could handle a full gallon like my big sister and finally a gallon in each hand like our bigger brothers. Our grandfather wanted us to develop a little muscle, I think, and didn't like to put the jugs in the cupboard or fridge with pine needls or sand on the bottom, so the challenge was not to set a jug down to rest on the five minute walk.

There was a greater challenge though. When a few gallons had been drawn from the tap, the pump would start up with a loud banging which sounded like: a-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel! My brothers were masters of terror and invented a little old man who lived in the pumphouse. They told Cathy and me that he resented us taking his water and hammered with his hammer to warn us away. If we took too much, he would burst out the door and come after us. I have a pretty clear image in my mind to this day of a wizened little man running after me with a hammer in his upraised had!

The twist to this horrible possibilty was that the boys were bigger and filled their jugs first. Just about the time their jugs were full, the pump would start up. they would run down the path, laughing, chanting: a-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel! along with the banging pump. Cathy and I were left quaking, sometimes even crying, yet more fearful of our our grandfather's rath if we didn't fetch our share of water. Even seeing our father go into the pumphouse to work on the pump, peering into that damp, cobwebby, half-underground, concrete chamber and seeing for ourselves that there was nobody at home, didn't entirely erase our fear. Until my grandparents finally had a well drilled at their own camp, my heart always thudded harder when the pump started up and The Little old Man in the Pumphouse started banging away with his hammer.

The Little Old Man in the Pumphouse

There’s a little old man in the pumphouse

My brothers both say that it’s true

But sometimes it’s fun to pretend to be scared

That he’ll jump out and run after you

The little old man in the pumphouse

Has skin that’s all mossy and green

And snaggley teeth and little mad eyes

He’s horrid and hairy and mean

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

He hammers with might and with main

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

Again and again and again

Who would be stealing my water—my icy-cold bubbling brew?

Children who dare

You’d better beware

Or I’ll hunt with my hammer for you!

There’s a little old man in the pumphouse

He pounds and he pounds with his hammer

We have to fetch water for Grammy and Baba

In spite of the clash and the clamor

Teddy and David are bigger

They make us girls fill our jugs last

And the hammer is pounding as loud as our hearts

As laughing they run away fast

Cathy can carry a big gallon jug

Switching hands without stopping to rest

Our brothers are strong, they can each carry two

But I like my half-gallon best

I can’t set it down because Baba will know

If there’s pine needles stuck to the wet

That drips down the glass on the side of my jug

Like icy-cold hot summer sweat

There’s a damp little room in the pumphouse

One time Daddy opened the door

And pulled on the string that turned on the light

I saw steps and the pump—nothing more

But the little old man in the pumphouse

Still hammers with all of his might

And tho’ I’m quite sure that he’s only pretend

He still makes me shiver with fright

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

He hammers with might and with main

A-huntel! a-huntel! a-huntel!

Again and again and again

Who would be stealing my water—my icy-cold bubbling brew?

Children who dare

You’d better beware

Or I’ll hunt with my hammer for you!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)